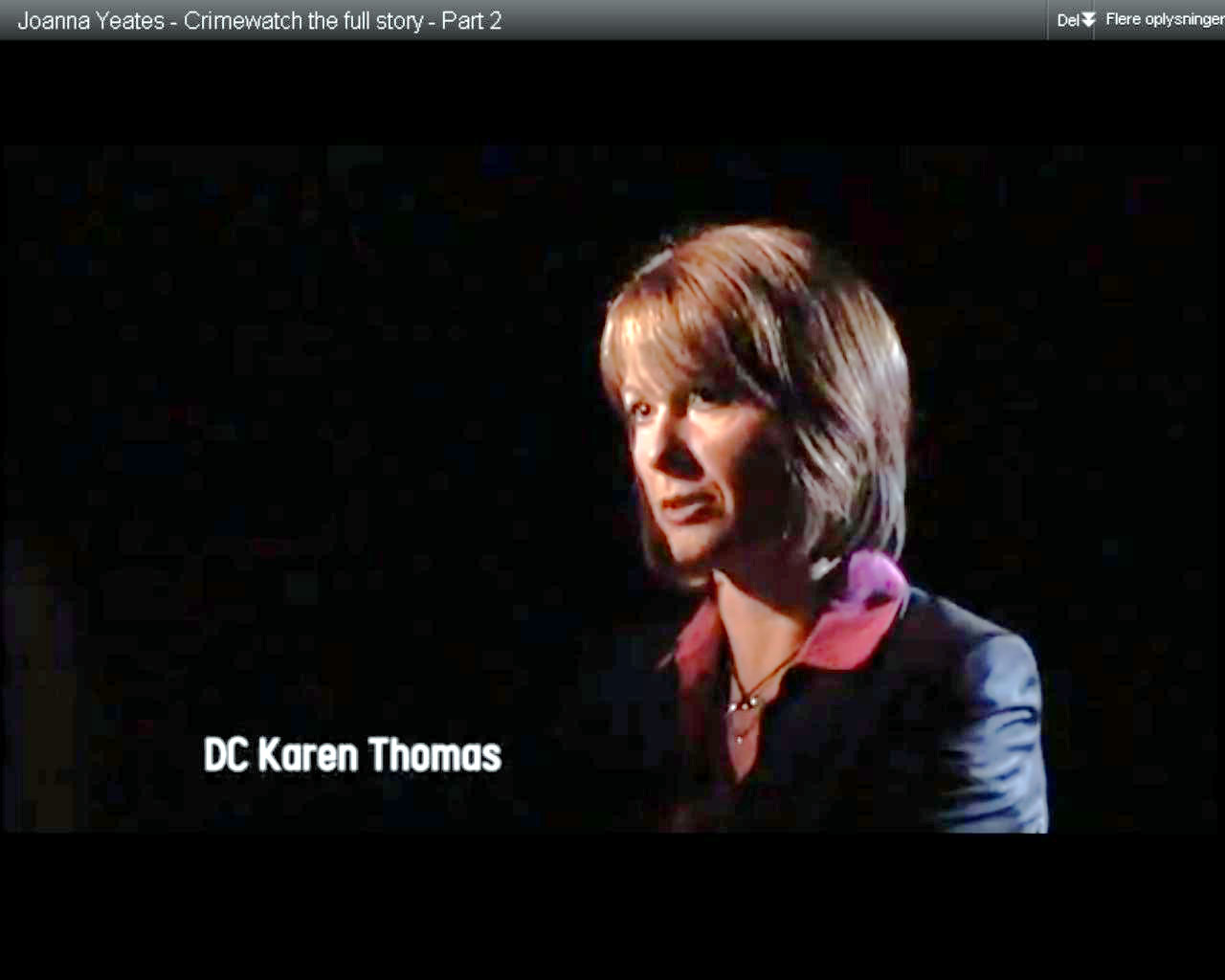

The Detective Constable who made Vincent Tabak a suspect

|

| Detective Constable Karen Thomas |

|

| Joanna Yeates |

|

| Crown Prosecutor Ann Reddrop, Head of the Complex Casework Unit |

|

| Vincent Tabak and Tanja Morson drove to Schiphol Airport on New Year’s eve to meet with DC Karen Thomas |

|

| Chief Constable Colin Port |

|

| Tanja Morson |

Flying to Schiphol would seem to be an “overly eager” response just to hear about an incident that could have been covered by a five-minute telephone call. It also emerged in court that Tanja too had been interviewed at Schiphol. So the movement of the landlord’s car in the night was probably just the pretext the Detective Constable gave in court for collecting the young couple’s testimony to what they remembered the landlord doing and saying while Joanna was missing. DC Thomas deceived and manipulated the jury about the purpose of the rendezvous.

Volunteering this information as a public-spirited response to the police’s appeal for any information that might help apprehend Joanna’s killer was held against the defendant as an effort to incriminate Christopher Jefferies falsely. Counsel for the Defence William Clegg QC failed to cross-examine DC Thomas about Mr. Jefferies’s version of the episode. If the landlord had denied that his car was facing the other way, then the prosecution would certainly have used this further to discredit the defendant. If not, then Mr. Clegg could have used the episode to discredit this key witness. But he didn’t.

|

| Did Detective Superintendant Mark Saunders also take part in the Schiphol interview? |

|

| Did Criminal Intelligence Analyst Lyndsey Farmery also fly to Schiphol? |

It is obvious from her subsequent testimony on 17th October 2011 that DC Karen Thomas used the protection of the Court to malign the Tabak family, who (together with the girlfriend) had gone out of their way to meet with her at Schiphol Airport. She told the court that both Tanja Morson and Vincent Tabak’s sister Eileen “fussed” over the defendant and expressed concern that he might be tired, “more than you would expect in the case of a grown man. I would describe the sister as a bit of a mother hen”, she added. How ill-bred can you get? Is it any wonder that Vincent Tabak’s girlfriend and sister “fussed” over him as it gradually dawned on them that the Detective Constable had begun to treat him as a murder suspect instead of as a witness?

Her testimony suggests that she did not caution Vincent Tabak that she was treating him as a suspect, as she should have done if the interview had taken place under British jurisdiction in accordance with the Police and Criminal Evidence act. However, the interview took place under Netherlands jurisdiction, so only a Dutch police officer would have had the authority to take his fingerprints and a swab of his saliva that could be used in a criminal case, and a Dutch lawyer furnished with the case papers would have had to be present to ensure that Vincent Tabak was properly informed of his rights under Netherlands law. Nothing in the Detective Constable’s testimony suggest that these requirements were complied with. Were the swab and the fingerprints obtained illegally? Did Chief Constable Colin Port contact one of his Dutch cronies from when he was stationed in the Netherlands in the 1990s to persuade the Schiphol authorities to turn a blind eye to his Detective Constable’s mission? Did DC Thomas deliberately avoid cautioning Vincent Tabak from a fear that he would decide to remain in the Netherlands and force Avon & Somerset Constabulary to apply for his extradition? If he really had killed Joanna, he would expect to be able to count on an examining magistrate in the Netherlands to reject an extradition request that was based on the weak case that was to be rubber-stamped by Bristol magistrate William Summers on 24th January 2011. On the other hand, if he knew he were a suspect for a crime he had not committed, he would have assumed, like all honest citizens, that his innocence would readily be established.

|

| (Photo: SWNS) |

The Detective Constable took Vincent Tabak’s fingerprints and a swab of his saliva. LGC Forensics did not need to enhance this swab to analyze his DNA, whereas they had already had four days to subject the low-copy-number partial DNA they had taken from Joanna’s body to their DNASenCE enhancement process. So the match for Vincent Tabak that the police subsequently claimed was found with the “DNA on Jo’s breast” ought to have been available within a few hours of the return of DC Karen Thomas from Schiphol. Why did A&S Constabulary wait nearly three weeks before arresting Vincent Tabak (while the national press daily accused them of incompetence) if there really was a match? Not until 19th January 2011 did the police leak to The Sun newspaper a claim that they had made “a major breakthrough” in their search for the killer. This referred to the “enhanced DNA” match that was the basis for his subsequent arrest, even though, in a TV documentary after Vincent Tabak’s conviction, A & S Constabulary acknowledged that this match could not have been used as evidence to charge him. The anonymous tip-off from a sobbing girl that the police had publicly alleged just after he was taken into custody had led to Vincent Tabak’s arrest was never mentioned in court. The real target of this deception was probably the duty solicitor and the barrister she would instruct, who would be fooled into instigating an abortive bail application.

The DNASenCE “enhancement” process used for the partial low-copy-number DNA also destroyed each of the samples, no one else would be able to verify this allegation.

When “Operation Braid” was started, the public was urged to come forward with any information that might lead to a conviction. When Vincent Tabak saw on TV in Holland that his landlord Christopher Jefferies had been arrrested, he got his girlfriend to telephone to A & S Constabulary to tell them that he believed the landlord had moved his car during the critical evening. They both recollected Mr. Jefferies asking for Vincent’s help to move his car because of the heavy snow that had fallen during the night after the murder. The landlord, a central person in the case, was never call as a witness to testify about the curious case of the car in the night. The Detective Constable told the court that it was this telephoned attempt to incriminate his landlord that had first aroused the police’s suspicions of Vincent Tabak. Questioned at the Leveson Inquiry, DCI Phil Jones emphasized that crimes get solved because of information submitted by members of the public. However, anyone who is ever tempted to help the police should bear DC Karen Thomas’s manipulative deceit in mind - and think better of it.

Why did DC Karen Thomas not suspect all the ex-pupils and ex-tenants of Mr. Jefferies who gossiped to journalists about him, and all the editors who published reports vilifying him?

The Detective Constable’s short testimony in court demonstrates that, even at the time of her trip to Holland, she had no more grounds to suspect Vincent Tabak than to make any other arbitrary person a suspect - nor did a motive nor other grounds than dubious forensic evidence ever emerge. There were thousands of potentially better qualified suspects in Clifton that night - men with parking tickets, men who beat their wives, men who cheated the Inland Revenue - and literally millions who could not have proved that they were not in Canynge Road at the time of the murder. A detective who shows no interest in the motive for something as serious as the murder of a stranger must be singularly lacking in imagination. Nor did the implications of his investment in his Ph.D for his motivation have any influence on her thinking. This reinforces the suspicion that the evidence the police needed to justify arresting him, and then charging him, would not be sufficient to convict him in court. This in turn reinforces the suspicion that a confession would be needed to obtain a conviction, and hence the suspicion that neither his plea nor his confession was sound. So the DC’s testimony is very significant. Nevertheless Counsel for the Defence did not cross-examine her.

|

| Vincent Tabak in Asda at Bedminster. Note the blur at the bottom left, where the timestamp has been erased from the video. |

According to the police’s Standards of Professional Behaviour, under the heading Authority, respect and courtesy, “Police officers act with self-control and tolerance, treating members of the public and colleagues with respect and courtesy.” Testifying in court that the accused’s sister and girlfriend “fussed over him as if he were not a grown man” and “I would describe the sister as a bit of a mother hen and very concerned that he was tired.” was in breach of this standard, intended to discredit the accused and his family, and disguise the fact that DC Karen Thomas was violating Netherlands sovereignty and the rules for questioning in a criminal case.

Most educated law-abiding citizens who talk to the police in connection with a serious crime would take it for granted that their absence of a motive and their good character (i.e., no previous convictions) would rule them out as suspects. Yet DC Karen Thomas completely disregarded these factors in Vincent Tabak’s case, and in so doing she violated his human rights. According to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), “All human beings are... endowed with reason and conscience...” (Art. 1) and “Everyone has a right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law” (Art. 6). She was therefore legally bound to acknowledge his ability to anticipate the consequences of his own actions and to distinguish between right and wrong, by establishing a concrete reason for him to commit the crime of which she suspected him. Instead of doing this, she treated him as an automaton, drawing up a list of circumstantial evidence which suggested that he could have committed the crime. Her grounds for making him a suspect were merely:

- He had no alibi for the time when the crime was believed to have been committed

- He changed his account of his movements about the time when the crime was committed

- He was in the vicinity where it was believed to have been committed

- His trip out to Asda for relatively minor purchases could have been a cover for dumping the body

- He volunteered evidence that could have incriminated his landlord

- He showed great interest in the removal of the front-door of the victim’s flat

- He was immature and needed to be fussed over by his elder sister and slightly older girlfriend

The Detective Constable’s undeclared agenda was also to build up a picture of Vincent Tabak as a potential suspect. DC Thomas was the police officer who established how vulnerable he was to being made a scapegoat:

- Vincent Tabak has no family in England

- He had been in England only three years

- He had been together with his English girlfriend only two years

- The only other person in England who knew him well was his boss at Buro Happold in Bath, Dr. Shrikant Sharma

- His newly widowed mother in the Netherlands cannot speak English

- His only brother is an engineer and newly divorced single father of small children in the Netherlands

- The strongest person in the family is his eldest unmarried sister, a scientist with a Ph.D employed by a major public health institute in the Netherlands

- The Chief Constable of Avon & Somerset, Colin Port, had been stationed in the Netherlands in the 1990s as an co-ordinator for the International War Crimes Tribunal sitting at the Hague.

Their silence implies consent. Mr. Clegg has also had war crimes briefs at the Hague. The role he played in the trial of Vincent Tabak suggests that he had become very good friends with Colin Port while he was in Holland. The silence of the Schiphol police and of the staff of the London Embassy indicates that maintaining good relations with Britain was more important to Holland than protecting the human rights of a highly skilled Dutch expatriate in another EU country. This has sobering implications for any EU national who works or studies in another member state.